Dispute Resolution HotlineDecember 16, 2014 Bite of a Bit: Calcutta High Court refuses to injunct investment arbitration against India

INTRODUCTIONIn a first of its kind case, the Single Judge of the Calcutta High Court (“Court”) on September 29, 2014 granted an anti-arbitration injunction (“Judgment”) in favor of Kolkata Port Trust (“KPT”) restraining Louis Dreyfus Armatures SAS (“Louis Dreyfus”), a French Company, from perusing any claim against KPT in the Investment Arbitration they have initiated against the Republic of India (“India”) under the Bilateral Investment Treaty (“BIT”) between India and France (“Investment Arbitration”). While doing so however, the court rejected KPT’s plea which sought to challenge the maintainability of the entire Investment Arbitration on several grounds, more particularly detailed herein below. This is a one of the first judgments by an Indian Court interpreting a BIT and it’s inter play with the Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (“Arbitration Act”). The Judgment lays down principle for grant of anti-arbitration injunction under Indian Law and adopts a narrow and pro-arbitration approach. However the Court misses the opportunity to answers certain questions which have been a matter of debate internationally, owing to the precarious jurisprudence surrounding the Arbitration Act and the absolute lack of legislative guidance with regards to India’s BITs. BACKGROUNDBackground of the Parties The genesis of the dispute is the awarding of a contract dated October 16, 2009 executed by KBT in favor of the Haldia Bulk Terminals Private Limited (“HBT”) (“Contract”) for operation and maintenance of berth nos. 2 and 8 of the Haldia Dock Complex of the Port Trust (“Project”). HBT, an Indian Company, was formed specifically for the purpose of carrying out the activities related to the Project and since July 23, 2009, is a subsidiary of an Indian Company, ALBA Asia Private Limited (“ALBA). Louis Dreyfus holds 49% of ALBA and the remaining is held another Indian Company, ABG Ports Limited (“ABG Ports”).Louis Dreyfus investment in the Project, through ALBA, is claimed to be approximately at US$ 16.5 Million (“Investment”).

Dispute between HBT and KPT Claiming breach, HBT terminated the Contract and commenced arbitration against KPT under the Contract seeking damages (“Contract Arbitration”). The Contract Arbitration is a domestic arbitration, seated in India and governed by Indian Law. In the Contract Arbitration, KPT has also preferred a counter-claim against HBT. Background of the Investment Arbitration On November 11, 2013 the Federal Government, the State of West Bengal and KBT received notice of claim issued from Louis Dreyfus in respect of Investment (“Notification of Claim”) under Article 9 of the India- France BIT. It is Louis Dreyfus’ claim that right from the very inception of the project, India, the State of West Bengal, KPT, and a number of authorities and agencies have consistently and deliberately, through their acts and omissions:

as a result of which the Contract was rendered redundant and HBT was left with no choice but to terminate its Contract with KPT. Louis Dreyfus claims that India, though its acts and omissions, has denied (i) fair and equitable treatment to Louis Dreyfus, (ii) failed to provide protection and safety to Louis Dreyfus' Investment in India and has ultimately (iii) indirectly expropriated Louis Dreyfus' Investment in the Project, thereby causing irreparable harm, injury and loss in clear violation of its obligations under the BIT. Pursuant to the Notification of Claim, Louis Dreyfus issued a notice of arbitration dated March 31, 2014, a notice of appointment of arbitrator on April 17, 2014 on India and notice dated May 19, 2014 once again calling upon India to enter appearance in the Investment Arbitration (“Notice of Arbitration”). India has denied and disputed the right of Louis Dreyfus to invoke the India-France BIT, however has nominated an arbitrator on its behalf under protest. Though KPT has not been named as a party in the Investment Arbitration, as the Notification of the Claim was addressed to KPT, the Arbitral Tribunal has resorted to notifying the KPT at every stage of the Investment Arbitration including vide letters dated August 13, 2014, August 15, 2014 and August 26, 2014. Proceedings before the Court Aggrieved by this, KPT filed the present proceedings before the Court seeking an injunction restraining Louis Dreyfus from taking further steps on the basis of Notification of Claim and Notice of Arbitration, essentially seeking an anti-arbitration injunction, against the Investment Arbitration, in its entirety. KPT’S CASE BEFORE THE COURTKPT sought the aforesaid anti-arbitration injunction on two grounds:

First Ground In support of its case under the first ground, KPT contended that:

Second Ground In support of its case under the second ground, KPT relied on a English judgment in the case of City of London v. Sancheti1 (“City of London”), to contend that the fact that under certain circumstance a State may be responsible under international law for the acts of one of its local authorities, or may have to take steps to redress wrongs committed by one of its local authorities, does not make that local authority a party to the arbitration agreement. KPT submitted that even if under the India- France BIT, India may be held responsible for any particular Act of KPT under no circumstances KPT could be treated as the party to the arbitration clause under the India- France BIT. Jurisdiction to grant anti-arbitration injunction In response to the Louis Dreyfus’s contention challenging the jurisdiction of the Court to adjudicate upon the proceedings initiated by KPT, KPT submitted that:

LOUIS DREYFUS’ CASE BEFORE THE COURTLouis Dreyfus primarily contended the jurisdiction of the Court to grant anti-arbitration injunction on the following grounds:

In response the First Ground raised by KPT, challenging the arbitration clause under the India- France BIT as inoperative, Louis Dreyfus submitted that:

COURTS DECISIONThe court found jurisdiction over the proceedings initiated by KPT and stated as follows:

The Court rejected KPT’s plea under the First Ground, challenging the arbitration clause under the India- France BIT as inoperative, stating:

Approving the decision in City of London, the Court accepted KPT’s under the Second Ground stating that:

ANALYSISThe facts of the case highlight the importance of BITs for protecting cross-border investments and show how the international community investing in India is using the same to secure performance of obligations by India. The Judgment lays down important guiding principles with respect to ability to obtain anti-arbitration injunction from court in India. The principles laid down seen to be pro-arbitration and in consonance with international jurisprudence on the subject. However, as the Judgment is delivered by a single judge of a High Court it cannot be regarded as a binding precedent and may undergo further judicial scrutiny and/or interpretation. The Judgment also rightly dismisses an attempt by a state instrumentality to derail investment arbitration under the pretext of multiplicity of proceedings and has safeguarded foreign investors from answering questions regarding applicability of BIT before national forums. However, the judgment misses the opportunity to clarify the applicability of BALCO to investment arbitration under Indian BITs. KPT’s contention that the arbitration agreement comes into force only once the Notification of Claim is submitted, has received international support from several authors and judicial/arbitral authorities. By concluding that Section 5 of the Arbitration Act, and thereby Part I, would be applicable to the present fact scenario, the Court may have ruled against long standing international jurisprudence, which may open a Pandora’s Box for future investment arbitration. 1 (2009)1 LLR 117 2 (2012) 9 SCC 552 DisclaimerThe contents of this hotline should not be construed as legal opinion. View detailed disclaimer. |

|

- If there is a valid arbitration agreement between the parties there is no escape from arbitration.

- Unless the facts and circumstances demonstrate that foreign arbitration would cause a demonstrable injustice, civil courts in India would not exercise its jurisdiction to stay foreign arbitration

- An anti-arbitration injunction can be granted only if:-

(a)Court is of the view that no agreement exists between the parties; or

(b)If the arbitration agreement is null and void, inoperative or incapable of being performed; or

(c)Continuation of foreign arbitration proceeding might be oppressive or vexatious or unconscionable

- Whether a claim falls within the parameters of a Bilateral Investment Treaty would only be decided by an arbitral tribunal, duly constituted.

INTRODUCTION

In a first of its kind case, the Single Judge of the Calcutta High Court (“Court”) on September 29, 2014 granted an anti-arbitration injunction (“Judgment”) in favor of Kolkata Port Trust (“KPT”) restraining Louis Dreyfus Armatures SAS (“Louis Dreyfus”), a French Company, from perusing any claim against KPT in the Investment Arbitration they have initiated against the Republic of India (“India”) under the Bilateral Investment Treaty (“BIT”) between India and France (“Investment Arbitration”). While doing so however, the court rejected KPT’s plea which sought to challenge the maintainability of the entire Investment Arbitration on several grounds, more particularly detailed herein below.

This is a one of the first judgments by an Indian Court interpreting a BIT and it’s inter play with the Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (“Arbitration Act”). The Judgment lays down principle for grant of anti-arbitration injunction under Indian Law and adopts a narrow and pro-arbitration approach. However the Court misses the opportunity to answers certain questions which have been a matter of debate internationally, owing to the precarious jurisprudence surrounding the Arbitration Act and the absolute lack of legislative guidance with regards to India’s BITs.

BACKGROUND

Background of the Parties

The genesis of the dispute is the awarding of a contract dated October 16, 2009 executed by KBT in favor of the Haldia Bulk Terminals Private Limited (“HBT”) (“Contract”) for operation and maintenance of berth nos. 2 and 8 of the Haldia Dock Complex of the Port Trust (“Project”).

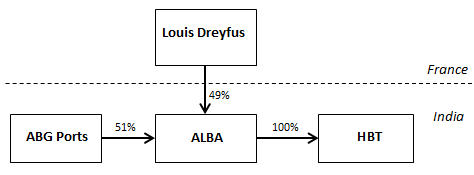

HBT, an Indian Company, was formed specifically for the purpose of carrying out the activities related to the Project and since July 23, 2009, is a subsidiary of an Indian Company, ALBA Asia Private Limited (“ALBA). Louis Dreyfus holds 49% of ALBA and the remaining is held another Indian Company, ABG Ports Limited (“ABG Ports”).Louis Dreyfus investment in the Project, through ALBA, is claimed to be approximately at US$ 16.5 Million (“Investment”).

Dispute between HBT and KPT

Claiming breach, HBT terminated the Contract and commenced arbitration against KPT under the Contract seeking damages (“Contract Arbitration”). The Contract Arbitration is a domestic arbitration, seated in India and governed by Indian Law. In the Contract Arbitration, KPT has also preferred a counter-claim against HBT.

Background of the Investment Arbitration

On November 11, 2013 the Federal Government, the State of West Bengal and KBT received notice of claim issued from Louis Dreyfus in respect of Investment (“Notification of Claim”) under Article 9 of the India- France BIT.

It is Louis Dreyfus’ claim that right from the very inception of the project, India, the State of West Bengal, KPT, and a number of authorities and agencies have consistently and deliberately, through their acts and omissions:

- created impediments to the implementation of the Project in an efficacious manner;

- compelled HBT to overstaff the Project;

- created impediments to the operation of the Project facilities in an efficacious manner in a normal, safe and conducive environment;

- failed to provide protection and safety to the Project facilities or HBT's personnel adequately or at all;

- financially crippled the Investment and the Project;

as a result of which the Contract was rendered redundant and HBT was left with no choice but to terminate its Contract with KPT.

Louis Dreyfus claims that India, though its acts and omissions, has denied (i) fair and equitable treatment to Louis Dreyfus, (ii) failed to provide protection and safety to Louis Dreyfus' Investment in India and has ultimately (iii) indirectly expropriated Louis Dreyfus' Investment in the Project, thereby causing irreparable harm, injury and loss in clear violation of its obligations under the BIT.

Pursuant to the Notification of Claim, Louis Dreyfus issued a notice of arbitration dated March 31, 2014, a notice of appointment of arbitrator on April 17, 2014 on India and notice dated May 19, 2014 once again calling upon India to enter appearance in the Investment Arbitration (“Notice of Arbitration”). India has denied and disputed the right of Louis Dreyfus to invoke the India-France BIT, however has nominated an arbitrator on its behalf under protest.

Though KPT has not been named as a party in the Investment Arbitration, as the Notification of the Claim was addressed to KPT, the Arbitral Tribunal has resorted to notifying the KPT at every stage of the Investment Arbitration including vide letters dated August 13, 2014, August 15, 2014 and August 26, 2014.

Proceedings before the Court

Aggrieved by this, KPT filed the present proceedings before the Court seeking an injunction restraining Louis Dreyfus from taking further steps on the basis of Notification of Claim and Notice of Arbitration, essentially seeking an anti-arbitration injunction, against the Investment Arbitration, in its entirety.

KPT’S CASE BEFORE THE COURT

KPT sought the aforesaid anti-arbitration injunction on two grounds:

- The arbitration clause under the India-France BIT is inoperative as between Louis Dreyfus and India, State of West Bengal and KPT.

- KPT is not a party to the arbitration clause in the India-France BIT and accordingly could not be dragged to the Investment Arbitration.

First Ground

In support of its case under the first ground, KPT contended that:

- Louis Dreyfus does not qualify as Investor under the India-France BIT;

- The scope of India-France BIT does not cover the nature of claim or dispute raised Louis Dreyfus;

- The substratum of Louis Dreyfus’ claim is the dispute between the HBT and KPT and hence amounts to multiplicity of proceedings;

- The entire cause of action Louis Dreyfus, as pleaded, is against KPT and India is impleaded only for the purpose of invoking the India-France BIT;

- KPT is a public sector undertaking of limited financial resources and conducting arbitration before an international body would be prohibitive and KPT would not be having means to conduct such proceeding effectively;

- The Investment Arbitration is oppressive, vexatious and mala fide.

Second Ground

In support of its case under the second ground, KPT relied on a English judgment in the case of City of London v. Sancheti1 (“City of London”), to contend that the fact that under certain circumstance a State may be responsible under international law for the acts of one of its local authorities, or may have to take steps to redress wrongs committed by one of its local authorities, does not make that local authority a party to the arbitration agreement.

KPT submitted that even if under the India- France BIT, India may be held responsible for any particular Act of KPT under no circumstances KPT could be treated as the party to the arbitration clause under the India- France BIT.

Jurisdiction to grant anti-arbitration injunction

In response to the Louis Dreyfus’s contention challenging the jurisdiction of the Court to adjudicate upon the proceedings initiated by KPT, KPT submitted that:

- There is no bar under Indian Law or the Arbitration Act, which restricts a civil court from granting an anti-arbitration injunction in respect of foreign arbitration.

- Section 5 of the Arbitration Act, which mandates minimum interference in arbitration proceedings and limits the jurisdiction of civil court to proceedings provided for under Part I the Arbitration Act, does not apply to arbitrations seated outside India to which only Part II of the Arbitration Act applies, as:

(a) The arbitration agreement between Louis Dreyfus and India would come only into existence upon the Notification of Claim, as prior to that arbitration clause in a BIT is at best a standing offer to arbitrate and upon acceptance by a qualifying investor of this standing offer to arbitrate gives to a binding arbitration agreement. Thus, the concerned arbitration agreement would be governed by law as declared by the Supreme Court of India in Bharat Aluminum Company and Ors. v. Kaiser Aluminum Technical Service, Inc. and Ors (“BALCO”).2

(b) The law prior to BALCO also provided that provisions of Part I did not apply to foreign seated arbitrations.

- Under Section 45 of the Arbitration Act a civil court has been vested with the power to decide whether arbitration clause in the India- France BIT is "inoperative or incapable of being performed" against KPT.

- Lack of provisions under Indian Law akin to those under Section 37 of the (English) Supreme Courts Act, 1981 (“English SC Act”) and Section 72 of (English) Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (“English Arbitration Act”) does not impinge upon a civil courts jurisdiction to grant anti-arbitration injunctions.

LOUIS DREYFUS’ CASE BEFORE THE COURT

Louis Dreyfus primarily contended the jurisdiction of the Court to grant anti-arbitration injunction on the following grounds:

- The India- France BIT was entered into 1997 and hence the arbitration agreement contained therein would be governed by arbitration law as it stood before the Supreme Court’s decision in BALCO.

- In pursuance to Section 5 of the Arbitration Act no judicial authority can intervene with an arbitration process, except where so provided by Part I of the Arbitration Act, notwithstanding anything contained in any other (Indian) law. The Arbitration Act does not empower a civil court to injunct an arbitration process.

- Anti-arbitration suit is ordinarily not maintainable, unless the statute gives a right to a civil court to exercise its jurisdiction against initiation of such proceeding. Provisions akin to Section 37 of the English SC Act and Section 72 English Arbitration Act are not present under Indian Law and hence the Court has no jurisdiction to entertain proceedings initiated by KPT.

- The arbitral tribunal has exclusive jurisdiction to rule its jurisdiction even with respect to existence or validity to the arbitration agreement.

In response the First Ground raised by KPT, challenging the arbitration clause under the India- France BIT as inoperative, Louis Dreyfus submitted that:

- The Contract Arbitration is of no relevance as the questions which may arise in that arbitration or the decision passed thereat cannot be looked into or be binding or relevant in the arbitration pending between the Louis Dreyfus and India. Hence, the principle of parallel proceedings and a possibility of conflict of decision have no application in two arbitrations.

- India- France BIT gives a right to an investor of the contracting nation meaning thereby the French National to invoke the arbitration clause in the treaty. The treaty is no uncertain term gives a cause of action to Louis Dreyfus to invoke the arbitration clause under the treaty, in the event, of failure on the India in protecting the investment of the French National, which cause of action is separate and distinct from that being adjudicated under the Contract Arbitration.

- KPT is not a party to the arbitration agreement between Louis Dreyfus and India and cannot challenge the arbitration agreement.

- Courts play a supportive role in encouraging the arbitration to proceed rather than letting it come to a grinding halt. Another equally important principle recognized in almost all jurisdictions is the least intervention by the courts.

COURTS DECISION

The court found jurisdiction over the proceedings initiated by KPT and stated as follows:

- Section 5 of the Arbitration Act is of general principle which would be applicable to all arbitration proceedings, irrespective of whether it is a domestic arbitration or a foreign seated arbitration.

- Although there may not be same and/or similar provisions in the Arbitration Act to the Section 37 of the English SC Act and Section 72 English Arbitration Act, the jurisdiction of a civil court to interfere is not completely obliterated as one could find that in Sec.45 of the Arbitration Act powers have been given to a civil court to refuse reference in case it is found that the said agreement is null and void, inoperative or incapable of being performed.

- Unless the facts and circumstances of a particular case demonstrate that continuation of such foreign arbitration would cause a demonstrable injustice, civil courts in India would not exercise its jurisdiction to stay foreign arbitration.

- Questions relating to arbitrability or jurisdiction or to staying the arbitration, might in appropriate circumstances better be left to the foreign courts having supervisory jurisdiction over the arbitration. Nonetheless in exceptional cases, for example where the continuation of the foreign arbitration proceedings might be oppressive or unconscionable, where the very issue was whether the parties had consented or where there was an allegations that the arbitration was a forgery the court might exercise its power. The court would pass an anti-arbitration injunction.

- The principle the court is required to keep in mind is that if there is a valid arbitration agreement between the parties there is no escape from arbitration and the parties shall be referred to arbitration and resolve their dispute through the mechanism of arbitration.

- In the following circumstances an anti-arbitration injunction can be granted:-

(a) If an issue is raised whether there is any valid arbitration agreement between the parties and the Court is of the view that no agreement exists between the parties; or

(b) If the arbitration agreement is null and void, inoperative or incapable of being performed; or

(c) Continuation of foreign arbitration proceeding might be oppressive or vexatious or unconscionable.

The Court rejected KPT’s plea under the First Ground, challenging the arbitration clause under the India- France BIT as inoperative, stating:

- Since KPT is not a party to India- France BIT the KPT cannot challenge the arbitration agreement. If anyone at all is aggrieved is India and KPT cannot espouse the cause of India.

- The Arbitral tribunal which has been duly constituted to adjudicate the Investment Arbitration would surely consider all objections with all seriousness as it deserves along with the objection.

- The approach of courts should be towards being pro-arbitration. Another equally important principle recognized in almost all jurisdictions is the least intervention by the courts.

- An investor under a BIT has been given certain special rights and privileges which is enforceable under the treaty. Whether the Notification of Claim falls within such parameters and Louis Dreyfus could be treated as an investor is a matter to be decided by the arbitral tribunal duly constituted under the relevant rules.

- In the event, the preliminary objections are overruled and the arbitral tribunal is of the opinion that the matter can proceed and continuation of such proceeding would not be a recipe for confusion and injustice. India would be required to contest the matter on merits.

Approving the decision in City of London, the Court accepted KPT’s under the Second Ground stating that:

- The arbitration agreement is only enforceable against the India and not against KPT.

- The continuation of any proceeding against KPT at the instance of the Louis Dreyfus would be oppressive

- KPT would not be bound to participate in the said proceeding.

- Louis Dreyfus is restrained from proceeding with the arbitral proceeding only against KPT.

ANALYSIS

The facts of the case highlight the importance of BITs for protecting cross-border investments and show how the international community investing in India is using the same to secure performance of obligations by India.

The Judgment lays down important guiding principles with respect to ability to obtain anti-arbitration injunction from court in India. The principles laid down seen to be pro-arbitration and in consonance with international jurisprudence on the subject. However, as the Judgment is delivered by a single judge of a High Court it cannot be regarded as a binding precedent and may undergo further judicial scrutiny and/or interpretation.

The Judgment also rightly dismisses an attempt by a state instrumentality to derail investment arbitration under the pretext of multiplicity of proceedings and has safeguarded foreign investors from answering questions regarding applicability of BIT before national forums.

However, the judgment misses the opportunity to clarify the applicability of BALCO to investment arbitration under Indian BITs. KPT’s contention that the arbitration agreement comes into force only once the Notification of Claim is submitted, has received international support from several authors and judicial/arbitral authorities. By concluding that Section 5 of the Arbitration Act, and thereby Part I, would be applicable to the present fact scenario, the Court may have ruled against long standing international jurisprudence, which may open a Pandora’s Box for future investment arbitration.

1 (2009)1 LLR 117

2 (2012) 9 SCC 552

Disclaimer

The contents of this hotline should not be construed as legal opinion. View detailed disclaimer.

Research PapersMergers & Acquisitions New Age of Franchising Life Sciences 2025 |

Research Articles |

AudioCCI’s Deal Value Test Securities Market Regulator’s Continued Quest Against “Unfiltered” Financial Advice Digital Lending - Part 1 - What's New with NBFC P2Ps |

NDA ConnectConnect with us at events, |

NDA Hotline |