Research and Articles

Hotline

- Capital Markets Hotline

- Companies Act Series

- Climate Change Related Legal Issues

- Competition Law Hotline

- Corpsec Hotline

- Court Corner

- Cross Examination

- Deal Destination

- Debt Funding in India Series

- Dispute Resolution Hotline

- Education Sector Hotline

- FEMA Hotline

- Financial Service Update

- Food & Beverages Hotline

- Funds Hotline

- Gaming Law Wrap

- GIFT City Express

- Green Hotline

- HR Law Hotline

- iCe Hotline

- Insolvency and Bankruptcy Hotline

- International Trade Hotlines

- Investment Funds: Monthly Digest

- IP Hotline

- IP Lab

- Legal Update

- Lit Corner

- M&A Disputes Series

- M&A Hotline

- M&A Interactive

- Media Hotline

- New Publication

- Other Hotline

- Pharma & Healthcare Update

- Press Release

- Private Client Wrap

- Private Debt Hotline

- Private Equity Corner

- Real Estate Update

- Realty Check

- Regulatory Digest

- Regulatory Hotline

- Renewable Corner

- SEZ Hotline

- Social Sector Hotline

- Tax Hotline

- Technology & Tax Series

- Technology Law Analysis

- Telecom Hotline

- The Startups Series

- White Collar and Investigations Practice

- Yes, Governance Matters.

- Japan Desk ジャパンデスク

M&A Hotline

May 5, 2023Reverse Flipping: Time to 'Internalise' Into India Inc!

INTRODUCTION

‘Flipping’ refers to the process of transferring the entire ownership of an Indian entity to an entity incorporated abroad, along with a transfer of the key assets such as intellectual property. The resultant structure is an Indian company becoming a wholly owned subsidiary of a foreign company, with the day-to-day operations being conducted in India. Effectively, the ownership of the entity is externalised abroad, whereas the value of such entity may continue to vest with the Indian entity.

While flipping is generally considered to be easier at the initial stages of the life cycle of an entity, mature structures have also flipped out of India in the last few years for a myriad of reasons. A predominant reason for flipping has generally been the access to a global pool of investors, ease of listing on overseas exchanges, higher valuations in stock exchanges abroad, broader customer base in new geographies, relatively easier regulatory regimes, founder preferences and taxation benefits accruing to interested international investors in their host jurisdictions.1 Singapore, Cayman Islands, United Kingdom and the United States of America have been popular examples of countries to which Indian entities have ‘flipped’.

However, there is a marked rise in ‘reverse flipping’ into India recently. As the name suggests, reverse flipping refers to the process of internalising through an integration of ownership and value of an entity back into India. Thus, the shares of the foreign and Indian shareholders (that were originally held at the foreign holding company level) are swapped for shares of the Indian company, pursuant to which the foreign companies / offshore holdings are dissolved or merged into the Indian entity and all the shareholders at the offshore level own the shares of the Indian entity. While this may have a few adverse implications (including tax implications) on the investors, the general motivation for a reverse flip is the increased certainty of an exit at a higher valuation in India.

In this article, we examine the Indian ecosystem to trace potential reasons for an increase in reverse flipping (alternatively referred to as “internalisation”) by entities and set out various considerations for entities considering a reverse flip into India in the near future.

Why is reverse flipping on the rise in India?

The Economic Survey 2022-23 has observed that there is a conducive environment for an increase in internalisation into India due to various initiatives, reforms and schemes targeted towards start-ups by the Government of India, greater access to capital within the prevalent private equity and venture capital setup, the growing maturity of Indian markets, and the recent changes in rules regarding round-tripping.2 Key government initiatives targeted towards start-ups include the schemes falling under the broader aegis of the National Initiative for Developing and Harnessing Innovations, the Fund of Funds for Start-ups and the Atal Innovation Mission, aimed at encouraging the development of indigenous products and providing financial assistance / seed funding to Indian start-ups during their formative years. With various reforms and the recent liberalization of regulations, the Government of India has not only enhanced the ease of doing business in India but has also reinstituted the lost faith of foreign institutional investors in India.

An important factor contributing to this trend is the changing attitude of founders and the management, who have begun acknowledging the value created, increased investment interest, brand relationships fostered and strength of the customer base in India and its direct proportionality to attractiveness through a near-future exit by way of an initial public offering (“IPO”). With concerns about the impending funding winter continuing to plague startups in 2023,3 difficult conditions in the global markets and the steep fall in the valuations of new-age tech firms, it has become imperative for entities to revisit and re-strategise their business models for organic growth and increased customer centricity. If the value associated with the work of these entities lies within India, a return to India may be more beneficial to their business operations and contribute to positive market perception. Even otherwise, there is a reduction in the administrative / managerial overhead expenses incurred and applicable statutory compliances to be adhered to, since the operations of the entity will only be limited to one country.

Established companies such as PhonePe4 and Pepperfry5 have recently internalised into India – which only demonstrates the increasing popularity of resorting to the process of internalisation.

Key considerations in respect of reverse flipping

While reverse flipping may prima facie seem desirable given its increasing popularity and a comparatively more supportive regulatory environment developing in India, it is important for entities, their managements and participating shareholders to evaluate several legal and commercial considerations that may arise while shifting their domicile back into India.

Some of these considerations include:

1. Structuring the internalisation

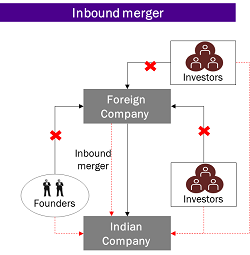

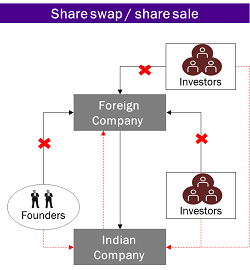

The most important step in the process of internalisation is finding the right structure which fits into the legal, regulatory and tax contours of the relevant jurisdictions in question. While an in-bound merger (whereby a foreign entity merges into the Indian entity, the assets and operations of the foreign entity are eventually owned and controlled by the Indian entity, and the shareholders of the foreign entity are issued shares of the Indian entity as consideration) seems to be the simplest of the structures for internalisation, we have also explored a share swap arrangement where the shareholders of the foreign entity swap their shareholding in such foreign entity with the shares of the Indian entity.

A diagrammatic representation of these structures (i.e. the in-bound merger into India and a share swap arrangement) is as depicted below:

|

|

|

[N.B.: In relation to both the aforesaid diagrams, the arrows in black indicate the structure of the entity prior to undertaking the reverse flip, that will be impacted by the reverse flip i.e. the shares currently held in the structure, that will be cancelled / swapped upon consummation of the inbound merger / share swap or sale (as applicable). The arrows in red reflect the steps and the resultant structure that will exist upon consummation of the reverse flip in either scenario.]

In India, the process of mergers is court-driven and needs to be approved by the National Company Law Tribunal (“NCLT”). According to Section 234 read with Section 230 of the Companies Act, 2013 (“CA 2013”), parties wishing to consummate a merger must approach the NCLT for prior approval by providing all material facts relating to the merger in a ‘scheme’. During the process of review of the scheme, the NCLT may call upon meetings of all members / creditors of the entity and send notices to other regulators such as the Registrar of Companies and Regional Director.6 Upon receipt of objections / representations from these regulators and authorities (if any), the NCLT will analyse the scheme and grant its approval. In India, the process of obtaining approvals for such schemes is long-drawn and takes at least 6-9 months.

Besides examining the applicable Indian laws, internalisation brings an additional layer of complexity in terms of requiring an analysis of necessary actions that may be required for the out-bound mergers under the corporate law of the host country in which the foreign entity is incorporated.

The challenges that may potentially arise differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. For instance, in Singapore, an outbound merger with an Indian entity has not been tested and may require prior clarifications and approvals of the regulators before effectuating one.7 In Cayman Islands, the dissolving entity is required to satisfy the domestic Registrar of Companies that the merger pursuant to which it is to dissolve: (i) is not prohibited by the charter documents of the company; and (ii) no outstanding petition for winding up / liquidation of the company is pending in any other overseas jurisdiction except for the proposed merger.8 Parallelly, the company must also call for a meeting of its Board of Directors to approve a written plan of the merger,9 and then submit all relevant documents for issuance of a ‘strike-off’ certificate indicating dissolution of the entity under Cayman company law.10 In Mauritius, reverse flips are likely to be subject to the provisions of Section 247 of the Companies Act, 2001 which prescribes the procedure for “short-form amalgamations” in case: (i) a company and companies that are directly or indirectly wholly owned by it are to amalgamate; or (ii) two or more companies, each of which is directly or indirectly wholly owned by the same company, amalgamate as one.11 Under the Delaware General Corporate Law applicable to Delaware outbound mergers, prior approval of the Board and shareholders of the amalgamating companies is required.12 However, the law specifically also provides that even if the resultant entity is a foreign corporation, it may be required to follow the process under this law in relation to any obligations / enforcement of any obligations as applicable to the resultant entity and arising from the merger.13 With all these considerations, there is an increased possibility of delay in timelines, since there is regulatory uncertainty that prevails within the two jurisdictions. Thus, in case internalisation is considered by way of a cross border merger, the success thereof would depend on approvals by the authorities and due regard to the timelines and procedures for consummation of such structures in all relevant jurisdictions.

2. Tax implications

If the reverse flip is implemented by way of an in-bound merger, the shareholders of the foreign amalgamating entity will be able to claim exemption from capital gains tax arising out of such transfer, subject to such transaction qualifying as an ‘amalgamation’ under the provisions of the Indian Income Tax Act, 1961 (“IT Act”). The term “Transfer” under the IT Act includes extinguishment and/or relinquishment of capital assets. Accordingly, in case a reverse flip is implemented by way of a cross-border merger (which does not meet the conditions set out under the IT Act to be considered an exempt transfer), it would tantamount to cancellation of shares of the foreign entity as held in the Indian entity and consequently, capital gains upon extinguishment of such shares may also be taxable in the hands of foreign entity.

However, if the reverse flip involves a swap of shares held by the foreign shareholders in the foreign entity with the shares of the Indian entity, the foreign shareholders will be subject to tax in India on the delta between the value of shares of the Indian entity at the time of such reverse flip and the cost of acquisition of the shares of the foreign entity.

As an example, the capital gains taxes paid by the shareholders of PhonePe (in case of swap of shares) during its shift to domicile in India was as high as almost INR 8,000 crores.14 Investors that would bear these taxes would generally advocate for robust exit provisions (generally, through an IPO) in exchange for such taxes, making the pressure of short to medium-term performance on the entity higher.

Further, as per the provisions of the IT Act, any income arising from a transfer of share or interest in a foreign company or entity, is taxable in India (in the hands of the foreign shareholders), if such share or interest derives substantial value from assets located in India in the manner set out in the IT Act. Accordingly, in case of a reverse flip by way of swap of shares, the indirect transfer tax provisions shall have to be evaluated, from the perspective of extinguishment of shares of the shareholders of the foreign company.

During structuring internalisation, it may also be important to consider potential concerns that may be raised by foreign investors of the tax assessment risk and vagaries of the taxation system in India, given that they will now be subject to tax in India.

Tax treaty benefits that were previously available to foreign shareholders may not necessarily be available to them in the resultant Indian entity, unless India has signed a Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (“DTAA”) with the country they are residents in. As an example, any investment in the shares of an Indian entity until April 1, 2017, by an entity resident in Singapore was grandfathered from capital gains tax in India. Accordingly, any capital gains arising from the alienation of such investments (if such investments are made after April 1, 2017) will be subject to capital gains tax in India as per the DTAA between India and Singapore.

In relation to the foreign shareholders, it is also important to consider the tax implications that will arise at the time of exit from the Indian entity in the near future by way of an IPO or a transfer.

Lastly, it is important to note that the accumulated losses available in the financial statements of the Indian and offshore level prior to internalisation may lapse and may not be available for set off if certain shareholding thresholds are breached.

3. Compliance with the Foreign Exchange Management (Cross Border Merger) Regulations, 2018 (“Cross Border Regulations”)15 and allied laws

As mentioned above, the process of in-bound mergers is broadly regulated by the provisions of Chapter XV of the CA 2013. The relevant rules are the Companies (Compromises, Arrangements and Amalgamations) Rules 2016. Under Rule 25A of these rules, prior approval of the Reserve Bank of India (“RBI”) is required for in-bound mergers. In this regard, the RBI framed the Cross Border Regulations which provides that merger transactions in compliance with these regulations shall be deemed to have been approved by RBI, and hence, no separate RBI approval should be required. In other cases, cross-border merger transactions shall require prior RBI approval.16

According to the Cross Border Regulations, issuance or transfer of securities to a person resident outside India by way of an in-bound merger (in case of internalisation, a transfer of shares to the foreign investors / shareholders) will have to be undertaken in accordance with the pricing guidelines, entry routes, sectoral caps, attendant conditions and reporting requirements for foreign investment as laid down under Foreign Exchange Management (Non-debt Instruments) Rules, 2019,17 along with due regard to the provisions of the recently enacted Foreign Exchange Management (Overseas Investment) Rules, 2022. Additionally, for all guarantees and outstanding borrowings of the foreign company which are obtained from foreign sources and become the borrowings of the resultant entity, the Cross Border Regulations prescribe that such guarantees and borrowings will have to comply with external commercial borrowing / trade credit norms or other foreign borrowing norms (as applicable) within two years from the date of the in-bound merger.18

Under the Cross Border Regulations, the resultant entity is not restricted from holding assets or securities outside India unless barred by the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 (“FEMA”) or the rules / regulations framed hereunder. In case such holding is barred, the resultant entity must sell such asset or security within a period of two years from the date the scheme has been sanctioned by the NCLT, and the sale proceeds shall be repatriated outside India immediately through banking channels.19 However, if such holding is not barred, they can be freely transferred in the manner prescribed by the FEMA and the rules / regulations framed hereunder20 – making transfer of assets such as goodwill and intellectual property feasible.

4. Feasibility of IPOs

For existing institutional investors, an exit within a definitive timeline is key to realization of the value of their investment. Since an IPO continues to be the one of the most preferred mode of exit for these investors, it becomes important for companies to demonstrate shorter and medium-term plans to list on the primary markets.

With the surge in successful IPOs on the Indian market in 2021 and subsequent reduced IPO activity across most of 2022,21 commercially, it will continue to remain difficult to determine whether the Indian market for IPOs will remain attractive for the resultant internalised entity. Although the trend is expected to change for the larger good in 2023,22 the overall market sentiment and reaction towards a to-be listed company’s products / services and sector at the time of a contemplated exit (i.e. once the NCLT approval for the merger is received), cannot be conclusively predicted.

Furthermore, existing investors will also have to consider the transfer restrictions prescribed by SEBI of the shares held by them. According to the SEBI (Issue of Capital and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations 2018, the revised non-promoter shareholder lock-in requirement for all shares held by such investor in the pre-IPO period, is 6 months from the date of allotment in the IPO.23

5. Press Note 3 (2020 Series) approvals (“PN3”)

Given that a reverse flip may entail the entry of foreign investors in India, it may require prior approvals from the Government of India as the PN3 may be triggered. According to the PN3, prior approval is required when an investing entity is situated in a country sharing land borders with India, or where the beneficial owner of an investment into India is situated in or is a citizen of any such neighboring country.24

Thus, it is important for entities considering a reverse flip to assess the applicability of PN3 to each of their foreign retail and institutional shareholders well in advance. However, currently, there are significant uncertainties associated with the procedures relating to the PN3 itself, ranging from lack of clarity about the scope of “beneficial owner” to an absence of clear timelines for the processing of PN3 applications.25 Additionally, any individuals who are the nationals of such neighbouring country will require prior security clearance from the Ministry of Home Affairs prior to accepting a directorship on the board of the Indian company.26 While the PN3 application can have the effect of delaying timelines for the restructuring, due to increased number of rejections of such applications in recent times,27 the parties will need to be equally prepared for a rejection, in which case the entire flip may flop.

6. Other regulatory and sectoral approvals

Apart from the PN3, numerous other regulatory and sectoral approvals may be triggered depending upon the sector that the entity is operating in. For instance, a prior approval of the Government of India / RBI may be required if the internalised entity is undertaking business in a sector falling under the ‘approval route’ as set out in the Consolidated Foreign Direct Investment (“FDI”) Policy of India.28

Approvals may also be triggered depending upon the nature of business or licenses held by the entities involved in the reverse-flip. By way of example, prior written approval of the RBI is required for “change in control” of non-banking financial companies29 and housing finance companies.30 Since the foreign entity will be dissolved and all shareholders will move into the Indian entity, there is a change in the control, ownership and shareholding structure (along with a likely change in the management) of such entity and accordingly, all applicable approvals linked to ‘control’, ‘management’ and / or ‘shareholding’ in an entity will have to be procured. As another instance, payment aggregators may also need to notify the RBI about any change in control or management, and the RBI may place restrictions upon the management depending on its examination of the declaration.31

An entity may also have to examine whether an intimation / approval of the Competition Commission of India (“CCI”) will be triggered as a result of the internalisation. Parties will have to evaluate whether there is an acquisition of control pursuant to the consummation of the structure and the details of the deal value / asset size and turnover of the entities involved. Depending on the structure finalized, a notification under the Competition Act, 2002, may be required to be provided to the CCI, not only by the entities involved but also the foreign investors (being acquirers).32

Accordingly, all the regulatory and sectoral approvals that will be required, not only in India but also in the host countries of the offshore entity, will have to be thoroughly analysed while assessing the structure and timelines for undertaking an internalisation into India.

7. Employee Stock Option Plans (“ESOPs”)

With respect to employees engaged by the foreign entity prior to internalisation, such employees can either continue their employment with the surviving Indian entity as part of the reverse flip or they can be discharged from the employment with the foreign entity after settling and paying them in full at the offshore level. In case the employees agree to the transfer of their employment to the Indian entity, any stock options granted / promised to those employees (outside India) will need to be structured as per the requirements under the Indian corporate laws and will need to be exchanged for stock options issued by the Indian company, post the flip. Issue of stock options by the Indian company to its non-resident employees and directors will additionally be subject to the entry routes, sectoral caps, attendant conditions and reporting requirements for foreign investment as laid down under Foreign Exchange Management (Non-debt Instruments) Rules, 2019.

Further, according to the Indian corporate laws, there must be a minimum cliff of one year from the grant of option of an ESOP before such ESOPs are vested.33 In the context of a reverse flip, entities may face objections from its employees who will be forced to wait for an additional period of 1 year and will not be able to exercise their vested options for such additional period until the statutory requirements are met, upon the migration of the ESOP plan into India.

While this may not directly impact the commercials of the reverse flip, entities must evaluate the profiles of employees holding ESOPs and consider potential objections that they may receive or increased attrition due to the disincentivisation of employees.

CONCLUSION

The valuations on Indian market are becoming attractive, and many entrepreneurs are realising that the markets, where their brand has relationships with customers, are expected to reward them better. It comes with no doubt that the increase in the number of start-ups and the internalisation of the domicile back into India will have economic benefits for India and will lead to a rise in creation of job opportunities. However, the presence of operations and shareholders across multiple jurisdictions leads to a variety of interconnected factors that will have to be collectively assessed and aligned while analyzing the feasibility of internalisation, to ensure that the results outweigh the considerations and hurdles for its consummation.

– Parina Muchhala, Ipsita Agarwalla , Khyati Dalal & Harshita Srivastava

You can direct your queries or comments to the authors

1See generally, “Box XI.5: ‘Flipping and Reverse Flipping: the recent developments in Start-ups”, Economic Survey 2022-23 (Government of India), available at https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/.

2Ibid.

3“India's startup economy stares at deepening funding winter in 2023”, Business Insider India (January 7, 2023), available at https://www.businessinsider.in/business/news/indias-startup-economy-stares-at-deepening-funding-winter-in-2023/articleshow/96807902.cms.

4Tarush Bhalla, “It cost PhonePe Rs 8,000 crore to come to India, says Sameer Nigam”, Economic Times (January 25, 2023), available at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/startups/about-20-unicorns-have-asked-about-domicile-shift-phonepes-sameer-nigam/articleshow/97307712.cms?from=mdr.

5Order of the National Law Company Tribunal on the Merger by Absorption between Trendsutra Cyprus Limited and Trendsutra Client Services Limited, available at https://ii1.pepperfry.com/media/downloads/Scheme-of-Amalgamation-1-feb.pdf.

6Section 230(5), Companies Act, 2013.

7See generally, Section 246, Insolvency, Restructuring and Dissolution Act 2018 (Singapore); Sections 212 and 215, Singapore Companies Act 1967 (Singapore).

8Sections 237(7), 237(8), 237(10), Part XVI, Companies Law (2020 Revision) (Cayman Islands).

9Section 237(7) read with Section 233, Part XVI, Companies Law (2020 Revision) (Cayman Islands).

10Section 237(14), Part XVI, Companies Law (2020 Revision) (Cayman Islands).

11See generally, Section 247(2), Part XVI, Mauritius Companies Act 2001 (Mauritius).

12See generally, §251 and 252, Title 8, Delaware General Corporate Law (Delaware, USA).

13§ 252(d), Title 8, Delaware General Corporate Law (Delaware, USA).

14Tarush Bhalla, “It cost PhonePe Rs 8,000 crore to come to India, says Sameer Nigam”, Economic Times (January 25, 2023), available at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/startups/about-20-unicorns-have-asked-about-domicile-shift-phonepes-sameer-nigam/articleshow/97307712.cms?from=mdr.

15Foreign Exchange Management (Cross Border Merger) Regulations, 2018, available at: https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11235&Mode=0.

16Regulation 9(1), Foreign Exchange Management (Cross Border Merger) Regulations, 2018.

17Regulation 4(1), Foreign Exchange Management (Cross Border Merger) Regulations, 2018.

18Regulation 4(3), Foreign Exchange Management (Cross Border Merger) Regulations, 2018.

19Regulation 4(5), Foreign Exchange Management (Cross Border Merger) Regulations, 2018.

20Regulation 4(4), Foreign Exchange Management (Cross Border Merger) Regulations, 2018.

21 “In India, IPO proceeds are down 56 percent in 2022 despite its biggest listing ever”, Economic Times (December 15, 2022), available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/markets/in-india-ipo-proceeds-are-down-56-percent-in-2022-despite-its-biggest-listing-ever/articleshow/96243119.cms.

22Bhakti Makwana, “The IPO momentum will continue in 2023 at least for small IPOs: Prime Database”, Business Insider (India) (January 10, 2023), available at https://www.businessinsider.in/stock-market/news/the-ipo-momentum-will-continue-in-2023-at-least-for-sme-ipos-prime-database/articleshow/96728596.cms.

23Please see our analysis of this development at: https://nishithdesai.com/NewsDetails/4804.

24Press Note 3 of 2020, available at: https://dpiit.gov.in/sites/default/files/pn3_2020.pdf.

25Please see our analysis of the PN3 and associated concerns at: https://www.nishithdesai.com/NewsDetails/8265.

26Please see our analysis of this development at: https://www.nishithdesai.com/NewsDetails/6147.

27See generally, Dhanendra Kumar, “Rationalise FDI approvals under PN3”, The Hindu Business Line (June 14, 2022), available at https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/rationalise-fdi-approvals-under-pn3/article65527759.ece (noting that 66 of 347 PN3 applications have been approved since 2020).

28Consolidated FDI Policy (Effective from October 15, 2020), available at https://dpiit.gov.in/sites/default/files/FDI-PolicyCircular-2020-29October2020_0.pdf.

29Direction 3, Non-Banking Financial Companies (Approval of Acquisition or Transfer of Control) Directions, 2015, available at https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_ViewMasCirculardetails.aspx?id=9833.

30Direction 45, Non-Banking Financial Company – Housing Finance Company (Reserve Bank) Directions, 2021, available at https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/content/pdfs/MD100017022021_A.pdf.

31Guideline 5.2, Guidelines on Regulation of Payment Aggregators and Payment Gateways, Reserve Bank of India, available at https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11822&Mode=0.

32Section 6(2), Competition Act, 2002.

33Rule 6(a), Companies (Share Capital and Debentures) Rules 2014.